I’ve loved Terry Gilliam’s work since I was a kid watching Monty Python on PBS. I saw Time Bandits at least five times in the theater. Brazil still knocks me sideways every time I see it and I find few scenes in film so lovely as Baron Munchausen and Venus waltzing in the air. I love Gilliam’s manic creativity, his juxtaposition of fun and collapse.

I wanted to love The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus as well.

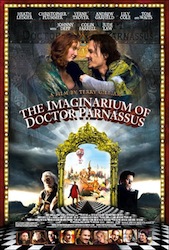

The story centers on a traveling show featuring Doctor Parnassus (Christopher Plummer), who first appears as a pseudo-sadhu, but as the story soon reveals, is a monk-turned-immortal due to a pact with the devil, Mr. Nick (the perpetually cool Tom Waits). He and Mr. Nick compete to win souls. With the help of his daughter, Valentina (Lily Cole, who is in no way convincingly 15 years old), a prestidigitator named Anton (Andrew Garfield) and assistant/sidekick Percy (Verne Troyer) who also seems to be immortal, though why he would be was never clear to me.

Doctor Parnassus has a mirror that people can walk through and enter his mind. Inside it’s a bit like Neverland, with everyone seeing their own imagination manifested around them. Within, they have the choice to go with Parnassus or Mr. Nick.

The troupe rescues a man hanging from a bridge. At first, he has amnesia, or appears to, but after a while they find out he’s Tony, a missing philanthropist. Tony (Heath Ledger in his final role) is charming, morally ambiguous and very attractive to Valentina, who, due to some poor choices on her father’s part, has been promised to Mr. Nick when she turns 16. And that’s as far as I am going with the plot synopsis.

Since the movie was not finished when Ledger died, his part was played by other actors in scenes when Tony enters the mirror. The stand-ins, Johnny Depp, Jude Law and Colin Farell, are all certainly more than competent actors, but the parts are brief and frantic.

I wondered, when I first heard about the movie, if the changes made after Ledger’s death would inspire creative re-writes or would just create confusion. I think it did neither. The confusion in the story wasn’t due to his death, nor did the death radically change the film’s direction.

What do the principal characters—the Doctor, Devil and Tony—want? This is the central, and least answered, question in the film. In part, they all want Valentina, and Valentina wants independence. Nick wants her simply as a poker chip. Tony wants her sexually. Doctor Parnassus wants her, but I’m not sure what for. To keep safe? Out of guilt? Or simply as a possession? His feelings for his daughter confuse me.

Tony changes all the time, and I’m not talking about the substitute actors. He skis slalom, self-serving on the right, helpful on the left, switching back and forth, but ultimately going downhill fast. Nick wants to gamble. He wants to play with Parnassus. He doesn’t really give a damn, literally or figuratively, about Tony until the end of the film. I love Tom Waits, so maybe my perception is clouded, but it seemed to me that, as devils go, Nick isn’t all that diabolical. More like Parnassus’s tricksy drinking buddy than an enemy. As Parnassus spends so much of the film being grumpy and drunk, it’s easy to prefer Nick.

I left the theater scratching my head, trying to figure out what I had just seen. In every Gilliam movie there are scenes of such mad, baroque decay that I can’t help but move back, trying simultaneously to distance myself from the dizziness and to widen my vision to take it all in. The Imaginarium has many such moments. What it doesn’t have, unlike Brazil or The Fisher King, is a cohesive narrative.

Familiar Gilliam images—chaotic vaudeville, heavy crumpled velvet curtains, little people in costume, gigantic heads of authority, grimy abandoned places and Bosch references—abound in the movie. The visuals range from the megalithic to the scatological to the elegant. He presents those images as well as he ever has, but in this case they seldom feel anchored to the plot. It’s one thing to take recurring images from dreams and put them in a film. Imaginarium feels not like a film of dream components but a dream itself, full of wonder, yes, but scattered.

Familiar Gilliam images—chaotic vaudeville, heavy crumpled velvet curtains, little people in costume, gigantic heads of authority, grimy abandoned places and Bosch references—abound in the movie. The visuals range from the megalithic to the scatological to the elegant. He presents those images as well as he ever has, but in this case they seldom feel anchored to the plot. It’s one thing to take recurring images from dreams and put them in a film. Imaginarium feels not like a film of dream components but a dream itself, full of wonder, yes, but scattered.

I am as big a fan of Gilliam as I have ever been, even though this movie didn’t work for me. I still regard him as one of the film world’s greatest fabulists and visionaries (a word too easily thrown around in Hollywood, but well deserved in his case). But even the greats lose control now and then.

When Jason Henninger isn’t reading, writing, juggling, cooking or raising evil genii, he works for Living Buddhism magazine in Santa Monica, CA.